It’s been exactly 20 years since the last Falstaff brewery in St. Louis shut down. Since then, a lot of other former beer giants, long-defunct, have been revived: Ballantine, Schaefer, Schlitz, and — just last year — Stroh’s. But nobody is asking for a return performance from Falstaff.

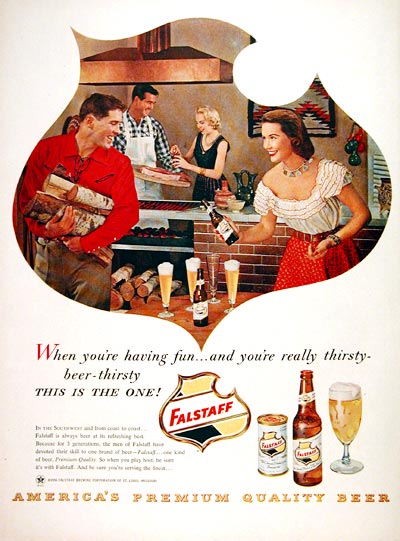

The brand had an impressive run, starting out back in 1903 as the St. Louis competitor of Anheuser-Busch. Both survived Prohibition, in Falstaff’s case by selling near-beer and smoked hams. In the 1940s the Falstaff mascot — Shakespeare’s hard-drinking, free-living clown — turned into a post-war advertising icon.

Falstaff was ahead of the game in sports sponsorship. With broadcaster Dizzy Dean and the St. Louis Cardinals and (later) Harry Caray and the Chicago White Sox, games became extended beer ads. Caray’s famous tagline was, “Ah, what I wouldn’t do right now for a plate of barbecue ribs and an ice-cold Falstaff!” In 1960 Falstaff ballooned into the third-best beer seller in the country, trailing only Schlitz and archrival A-B.

Things started going downhill in 1965, when Falstaff tried to acquire famous brewer Narragansett in an unwelcome pass at the northeastern beer market. Anti-trust litigation dragged on into 1973. Falstaff had to go all the way to the Supreme Court, and won; but the battle bled it white, the very definition of a Pyrrhic victory.

Falstaff’s ownership continued its over-acquisitive ways, buying up dying or closed breweries all over the country. It turned out to be a bad strategy, dangerously decentralizing production instead of modernizing the facilities they already had.

By 1975, there wasn’t much left to do but start over and hope for the best. Falstaff was sold to a tycoon named Paul Kalmanovitz, whose big plan was to eliminate all marketing, fire hundreds of longtime employees, and slash expenses to the bare bone — “like Grant through Richmond,” as one reporter said at the time. There was a lockout, an SEC investigation, and hard feelings all-around. Beginning with the landmark plants in St. Louis, one by one the Falstaff breweries across the country went dark.

Falstaff staggered on until 2005, as a licensed property of Pabst (the successor of Kalmanovitz’s holding company) but made under contract by other breweries. It sold a mere 1400 barrels in 2004, and the following June Pabst threw in the towel.

Nowadays, reviving dead beer brands is what Pabst does — Ballantine and Stroh’s being their latest resurrections. Narragansett too, in a bit of poetic justice, has found new life thanks to nostalgists. But Falstaff already had its shot at stardom, and there’s little reason for Pabst to give it another.